Business Owner Shares His Quest to Give Jobs and Hope to Ex-Offenders

September 17, 2019

Harrigan Solutions Turns Downtrodden Workers Into High Performers

March 20, 2020By: John Schmid, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

A little more than two years ago, veteran Wisconsin entrepreneur Bill Harrigan ripped up all his old business plans and relaunched Grafton-based Harrigan Solutions around ideas that aren’t taught in business school.

The man with a marketing degree immersed himself in brain science. Harrigan was determined to hire folks many might turn away — people with unresolved psychological traumas that stem from exposure to extreme violence, neglect, abuse and abandonment. Most of his 30 current hires are ex-offenders.

“This is about neuroscience,” Harrigan said about the job-training curriculum he designed.

Harrigan Solutions belongs to a growing handful of pioneers who are experimenting with new ways to integrate trauma-responsive practices directly into the workplace.

It’s a radical idea to some, not least because trauma-informed practices can trigger long-suppressed and painful past experiences.

Harrigan has seen the trauma data, which has been validated around the world. Unless those with invisible wounds begin to heal, people coping with neurological trauma statistically are prone to aggression, mental illness, drug abuse, prison, homelessness and dissociation — not unlike symptoms seen in some military veterans.

Critical to economists, researchers concur, is that chronic unemployment and generational cycles of poverty also trace back with statistical probability to homegrown, nonmilitary trauma.

“We found that 100% of the applicants have been exposed to trauma,” said Bill Krugler, whose nonprofit, Milwaukee JobsWork, has been helping develop a separate pilot program of trauma-responsive job training.

Trauma knows no boundaries

The same data consistently show that trauma-responsive workplaces have applications far beyond the nation’s high-trauma urban centers, such as Milwaukee. Data collected in the last decade reveal an epidemic of civilian neurological trauma across the American population — rural, urban and suburban — as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel has reported in a two-year series of stories called “A Time to Heal.” As a share of the population, measures of trauma were as high in places like Janesville, Racine and rural northern Wisconsin as they were in Milwaukee’s central city.

And no ethnicity or geography seems immune from post-traumatic stress in American society. Harrigan recruits from Kenosha and Milwaukee to Marinette and the Fox Valley. In the case of U.S. prisons, research reveals a population made up almost entirely of people with histories of childhood trauma.

It’s a well-intentioned but tricky ambition — to hire and to heal at the same time. There are only a few programs around the nation. Some are still in early stages. Mostly, there’s only anecdotal results on what works and what doesn’t.

But none of them looks like conventional one-size-fits-all job programs.

In Milwaukee, one of the earliest was launched last year by public health researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. That program accepts low-income applicants for transitional or temporary jobs subsidized by the state. The program screens job candidates for trauma exposure as well as trauma symptoms.

It makes for unusual job interviews. Typical questions include: Were you ever attacked with a gun or knife? Did anyone beat you as a child or force you to have sex? Were you ever abandoned or homeless? Assuming the assessments uncover symptoms of post-traumatic stress, the program refers the applicants to therapists, addiction counselors or social workers as part of their job training.

The Milwaukee pilot — dubbed Healthy Worker, Healthy Wisconsin — is in its third year under a five-year grant from the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

Krugler’s Milwaukee JobsWork is one of the partners in the Healthy Worker pilot, placing trainees in janitorial or landscaping services. “We developed a network of ‘stability employers’ willing to hire, knowing (the job candidates) aren’t always ready and might stumble and might miss work some days,” Krugler said.

One of the biggest challenges involves the shame of mental illness. Krugler said applicants hesitate to accept help and don’t routinely keep their appointments. Program planners are working on reducing stigma, case by case.

‘What happened to you?’

However the programs are modeled, the first rule of trauma-informed work is to discard conventional questions, such as “What’s wrong with you?” Instead, trauma practitioners ask an entirely new set of questions along the lines of “What happened to you?”

In Harrigan’s case, he sits down with each new hire and talks to them “until their lives spill out.”

His own self-styled program uses assessments to understand the candidates’ “mental models.” That helps explain how each person’s life experiences have conditioned their personal beliefs — or in some cases, trigger the auto-repeat loops of painful traumatic memories.

Harrigan created six crews. Like a staffing agency, he “embeds” them into other private-sector construction crews, food processing companies or metal fabrication shops. The crews put in full-time hours. Each crew, in turn, has a crew chief whose job is half supervisor and half recovery coach. “The crew chief is there to pounce on micro-progress,” Harrigan said.

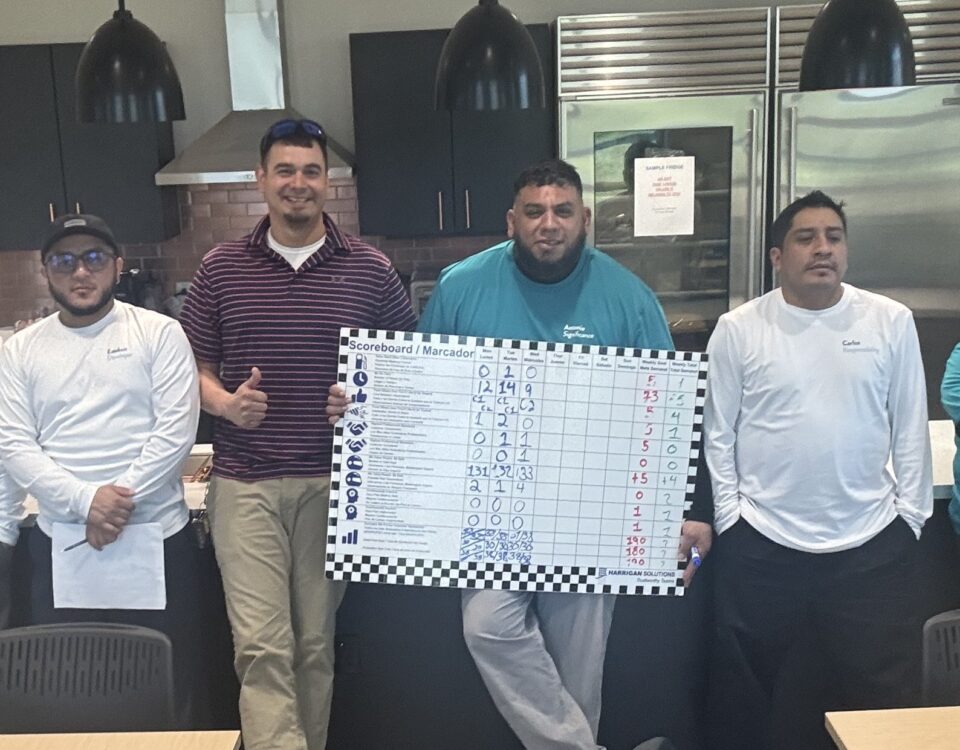

Photo: Mike De Sisti – Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Harrigan has no formal credentials in mental health other than his own high-trauma childhood in suburban Milwaukee. Without divulging details, he said he scores a five on a standardized score of trauma exposure, which is known as the Adverse Childhood Experience survey, or ACE test. Scores of four or higher statistically tend to be high risk for later life problems such as mental illness, aggression, and drug use.

“I sort of understand this from the underside,” Harrigan told the Greater Milwaukee Committee.

Outside Milwaukee, one of the best-known trauma-care job programs lies in Los Angeles, which claims a successful track record in hiring, healing and clean drug tests. It’s called Homeboy Industries and began life as a conventional make-work jobs agency. Its original motto was: “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.” For years, Homeboy proudly emblazoned the bullet-stopping aphorism on posters and T-shirts.

But the man who coined the catchphrase now disavows it. Father Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest who founded Homeboy and continues to run it, now argues that more than two decades of job placement haven’t stopped the bullets.

“No gang member would be caught dead talking to therapists, but now everyone is in therapy,” Boyle told the Journal Sentinel last year.

The role of SWIM in Milwaukee

Within Milwaukee, the idea of trauma-focused job training got a boost Monday at a meeting of the Greater Milwaukee Committee, a consortium of regional business and civic leaders. The event was moderated by Mike Lovell, president of Marquette University and founder of a collective of social agencies, nonprofits, clinics and university researchers that are engaged in trauma-responsive work. Lovell calls the collective Scaling Wellness in Milwaukee or SWIM.

Milwaukee will not reach its potential, Lovell told the business group, unless it learns to recognize the root causes of trauma and begins to change an environment that seems to traumatize people faster than they can heal.

“You have to change entire systems, and that takes a lot of sustained effort,” Lovell said.

The view of trauma researchers often flies in the face of conventional thinking about jobs. Trauma researchers point out that 50 years of anti-poverty programs, entitlements and subsidized jobs programs — as essential as they are — never stopped the unrelenting downward spiral in cities like Milwaukee.

It’s a phenomenon that Frank Cumberbatch encountered more than a decade ago when he worked as a City Hall aide. He was tasked with helping create programs to train a new generation of welders. Millions of dollars were spent. In theory, the training virtually ensured a good-paying job, not least because welders are perennially in short supply in Milwaukee’s metalworking industries.

The industrial employers themselves often were located near pockets of concentrated unemployment, seemingly ensuring high odds of success.

And yet, only about one in 50 actually graduated then got and held a job, Cumberbatch recounted, also speaking at the Greater Milwaukee Committee. “I couldn’t figure it out,” he said, echoing the view of baffled business leaders.

These days, Cumberbatch believes he knows the answer. He’s active in SWIM.

“I realized the problem is not the ability to work. It’s all the trauma that goes way back in these men’s lives,” said Cumberbatch, who now works as vice president for engagement at Milwaukee-based Bader Philanthropies.

Also speaking at Monday’s civic event was Ralph Metzner, an executive at FEI Behavioral Health, a metro Milwaukee consultancy that integrates psychology and therapy into the workplace.

Post-traumatic stress is so prevalent in the city and the nation that trauma-informed job programs are indispensable, Metzner said. At the same time, the unemployment rate is low, labor markets are tight, and the pool of job candidates for almost any field are more limited than usual.

The economy can’t afford to have so many sidelined by psychological afflictions, Metzner said. “You have no choice but to make them employable.”